Prince’s Estate Wants Prince.com: Understanding Cybersquatting

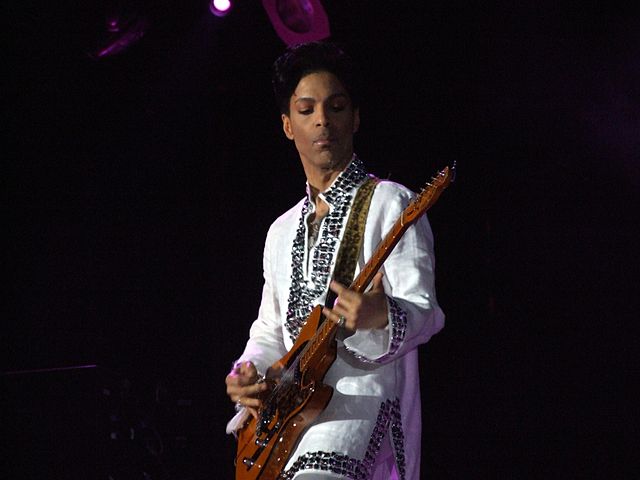

Ever since the tragedy of Prince’s untimely passing, his estate has been in one lawsuit after another to ensure the safety of the legacy of the famous songwriter. It’s probably no surprise given the empire and brand built on Prince’s name, but Prince had an enormous amount of value associated with his body of work and his very name. It is the latter portion of this that the estate has been trying to protect most recently. On July 25th, the estate brought a complaint against a domain name purchaser business known as Domain Capital in order to regain control of “prince.com.”

They have brought a lawsuit alleging that Domain Capital is cybersquatting on the domain name in a bad faith attempt to take advantage of Prince’s legacy, notoriety, and three trademarks on his name. Cybersquatting and actions to get back a domain name are actually fairly common.

However, they are normally brought under the Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP) of the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN). Instead, Prince’s estate has used the much less common method (due to the increased time and expense) of suing under the Anticybersquatting Consumer Protection Act (ACPA).

Prince, full given name, Prince Rogers Nelson, had a number of trademarks on his name–something he was capable of doing, as we’ll discuss later, due to how well known his name was. The lawsuit centers around the confusion between the domain name and these marks. Cybersquatting is, as mentioned, more common than you’d think.

However, the law and rules around it are not particularly widely understood. What’s more, big domain name purchasers such as Domain Capital are fairly common and clever about how they buy domains, often targeting things such as names that are difficult to trademark and offering to sell them for a few thousand dollars–generally less than the cost of litigating is a cybersquatting action.

It’s important to understand how and when you should proceed when you’re trying to secure a domain–whether it’s for an enormous empire such as Prince’s brand and name or for your small business. Let’s take a look at exactly how these laws work and how Prince’s case is moving forward.

What is Cybersquatting? Understanding the ACPA and ICANN

What is Cybersquatting? Understanding the ACPA and ICANN

Cybersquatting is essentially sitting on a domain name (a web address such lawblog.legalmatch.com) with the intention of taking unfair advantage of that mark–whether through implying you are something you’re not, attempting to extort a trademark holder when they try to purchase the domain, or another bad faith purpose.

Prince has taken the route of suing under the ACPA, which makes it a civil cause of action to register, traffic, or use a domain name that infringes or dilutes a trademark or name. Generally, when the expensive option of an ACPA lawsuit is chosen, it’s because the trademark holder in question wants to either make an example for future cypbersquatters and take advantage of the fact that ACPA lawsuits offer more remedies than the faster, cheaper ICANN options.

With an ACPA lawsuit, you can do more than just cancel a domain name or have it transferred to you–you can receive money damages or both your actual damages or between $1k and $100k per domain name in statutory damages.

A successful ACPA suit can be brought against the registrant of a domain name if you own a trademark and the registrant:

- Has a bad faith intent to profit off your mark; and

- Registers a domain name that either infringes (is identical or so similar to your mark that it’d confuse the public as to source or sponsorship) or dilutes (tarnishes or reduces the value of a particularly famous mark) your mark.

An ACPA suit can also cover a situation where somebody registers your name. A court looks at the totality of the circumstances in deciding whether a registrant has registered a domain name in bad faith, but the statute itself specifically looks to:

- Your intellectual property rights in the domain name;

- Whether the domain name includes your name;

- How well known your name or mark is and how much the public associates it with you;

- Whether the person you registered the domain actually uses it to sell their own goods and services;

- Whether the registrant uses the domain name at all for non-commercial purposes;

- Whether they got the domain with the intent of diverting customers by misrepresenting you they are or to tarnish your mark or name;

- Whether the registrant purchased the domain just to sell it for a profit and never actually used it; and

- Whether the registrant used false information to register the domain, and whether they have more than one domain names that would violate the ACPA.

ACPA suits generally do not succeed if the domain is registered with the intent of lampooning or criticizing you or whatever your trademark is associated with for First Amendment reasons.

In Prince’s case he was both born Prince Rogers Nelson, had a number of trademarks on his name (often tricky to do as a mark on a surname, nickname, or pseudonym needs to be especially well known to be successfully registered), and was obviously extremely famous.

The domains in question are both his name and his mark. Domain Capital is in the business of sell domain names, with 43 for sale on its website. They’ve also been forced to transfer a number of marks under ICANN actions which means they were improperly registered.

The actual prince.com site has no use whatsoever and is just a blank page. All this taken together cuts pretty strongly in favor of Prince’s estate on the ACPA claims. However, nothing is certain when it comes to a court case in as early stages as this one.

As mentioned, the Prince estate has been in a bit of legal frenzy to ensure the intellectual property and other rights Prince left behind to the beneficiaries of his estate upon his untimely passing. This aggressive approach is probably why they’ve chosen to file an ACPA suit as opposed to pursuing the much faster and cheaper Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP) offered by ICANN. An overwhelming portion of cybersquatting disputes, including every other action against Domain Capital, are resolved via UDRP.

The requirements to succeed in a UDRP proceeding are very similar to an ACPA proceeding. If you have a mark (UDRP proceedings don’t cover personal names) you will succeed if a registrant’s domain name infringes your mark, they have no rights or legitimate interest in your mark, and they registered the domain name in bad faith.

Bad faith is determined in a similar manner to an ACPA case. However, unlike an ACPA case, a UDRP proceeding doesn’t have the time and expense of a full trial and is simply heard by a single third party–usually a trademark attorney. They tend to be favorable to mark holders seeking to transfer or cancel a domain name. A UDRP complaint can be easily and quickly started through the ICANN website, although there are fees associated with the process and it is usually worth at least briefly consulting an attorney before filing.

How to Properly Register a Domain Name

Prince’s has a strong case for cybersquatting, but every day people are registering domain names and not using them immediately. This isn’t cybersquatting by itself. It’s quite common to register a domain name for future use and there’s no requirement you use a domain name you register.

With that in mind, if you’re running a business or just looking to the future it can be worth registering a domain name for use either now or later to avoid the expense of bringing a lawsuit such as the one brought by Prince’s estate or even just have to pay the fees on a UDRP proceeding.

There are quite a few services which act as domain registrars that can help you get a hold of a domain, although any site that guarantees it can get you any domain name is probably not totally on the up and up. Domains themselves are simply on a first come first serve basis.

The ICANN website has a number of suggested registrars if you aren’t sure whether the registrar you’re looking at is legitimate. An example of a registrar is the Public Interest Registry which handles all domains ending in .org. Once registered, you’ll have to periodically renew your domain registration. If you accidentally let a domain lapse, you generally have a 30 day grace period to fix your mistake before somebody can take it.

If you’re looking for a domain but it is taken, you can often find out who owns it by using the WHOIS search function through the ICANN website. If WHOIS is inaccurate you can also file a correction with ICANN. Once you know who owns a domain name you’re interested in you can better assess whether they are cybersquatting and what action you should take.

However, often you may find that you’ll simply have to make an offer to purchase the domain name–although an owner won’t necessarily sell to you. The larger domain name sellers can be fairly sophisticated when it comes to seeking out domains that are a difficult to challenge and offering prices slightly below what a lawsuit would cost.

Prince’s estate’s cybersquatting case may be high profile due to the parties involved. However, the truth is that domain names are a part of business whether you’re a rock superstar or a mom and pop business. If you own a business in the modern era, you likely need a web presence and holding on to domain names which are associated with your business is often a very good idea.

Jonathan Lurie is a Founding Partner of The Law Offices of Lurie and Ferri (Contact Info). He primarily handles business law, employment law, and intellectual property issues, but works with all types of civil matters. He is a Vice-Chair of the Sports and Entertainment Interest Group of the California Intellectual Property Section and has won awards for his knowledge of intellectual property, start-up business issues, and California civil procedure.

Comments