Attorney General Sessions Wants to Look at Your Phone

A backdoor from tech companies like Google and Apple allowing access to encrypted information stored on suspects devices has been something on the federal law enforcement wish list for some time. Similarly, there has been a push and pull between law and enforcement and tech companies over how much access these tech companies allow the government when it comes to the stored information of customers.

For instance, just a few years ago an email service known as Lavabit closed its entire business after refusing to comply with a court order allowing the U.S. government broad access to user emails. The exact breadth of the order was and is confidential. but it was enough that the company chose to close its doors rather than comply. The government has also turned to outside sources such as grey hat hackers to access password protected information on an iPhone. This led to an odd reversal of the usual dynamic where Apple was asking the FBI to reveal the security vulnerability in their own technology.

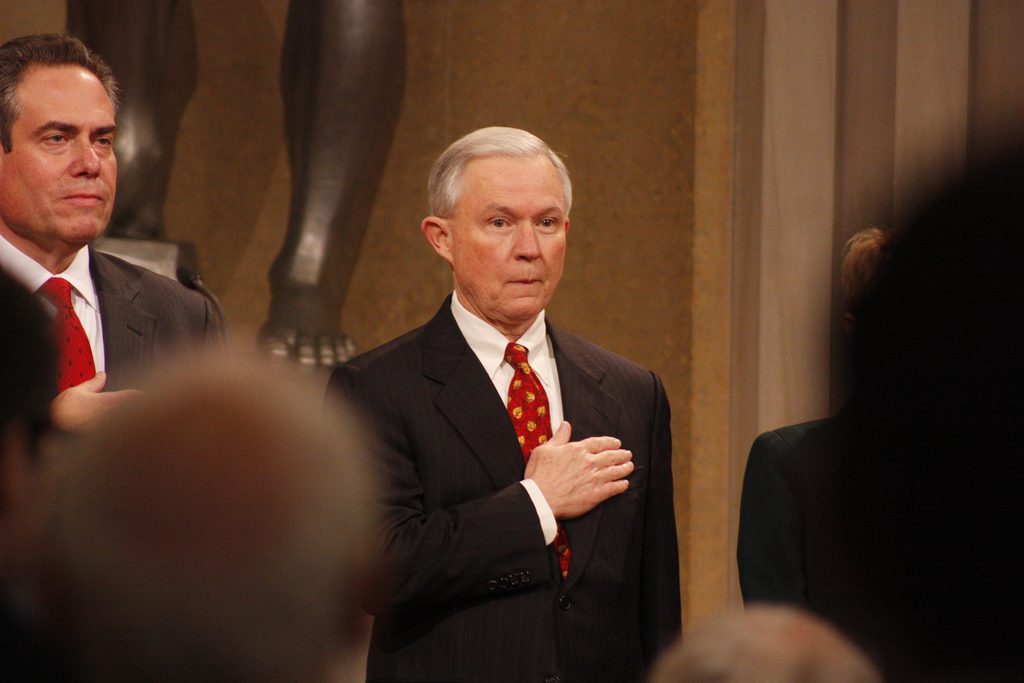

There is obviously a push and pull between the government’s interests in security and the public’s expectation to privacy in communications sent online and information stored through online services and on private phones, computers, or other devices. However, AG Jeff Sessions doesn’t think there’s much debate. Sessions has recently condemned tech companies for blocking access to encrypted data on mobile phones. He complains that tech companies have blocked FBI access to around 7,500 devices in the last year. He also says this is an act supporting terrorism.

Privacy vs. Security Under the Constitution

Regardless of how you feel about the balancing act between security and privacy, Sessions’ position is an immense oversimplification of an incredibly complex legal situation. Privacy rights come from many sources. These include state laws, statutes applying to specific situations and a more nebulous privacy right to privacy which the Supreme Court has ruled can be imputed from the combination First, Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Ninth Amendments–this is referred to in law as the penumbral rights of privacy and includes quite a few rights. Perhaps most relevant here is the Fourth Amendment right against unreasonable search and seizure.

The strength of this right generally hinges on a person’s reasonable expectation of privacy. It’s agreed that this is quite strong when you’re in your home, but the strength of your expectation of privacy varies drastically depending on the situation. How the right applies to data is a complicated situation–it’s generally agreed to apply to a locked phone as you’ve taken steps to ensure the privacy of the information on that phone–the same could generally be extended to a password protected computer or other device.

This kind of shoots in the foot AG Session’s assertions that not allowing the government to bypass these protections is a legally reprehensible action akin to supporting terrorism. At the very least, a broad assertion that every situation where tech companies decline to provide access to a phone is a bit rich when that information is often constitutionally protected from search without a warrant.

This kind of shoots in the foot AG Session’s assertions that not allowing the government to bypass these protections is a legally reprehensible action akin to supporting terrorism. At the very least, a broad assertion that every situation where tech companies decline to provide access to a phone is a bit rich when that information is often constitutionally protected from search without a warrant.

But when it comes to seeking information from a third-party such as a tech company the protections on this information become even more complex. The Fourth Amendment generally considers you to have relinquished your expectation of privacy when you knowingly reveal that information to a third party. The key words here being “knowingly reveal.”

It’s undisputed that you entrust the security of an enormous amount of information to third parties–storing information on the cloud, using an email service provided by another, sending a message through a third-party’s service, basically any situation which involves storing information on a third-party server–an incredibly common situation in today’s digital age. Where this happens, no warrant is required to access your information–instead the government only requires a subpoena and prior notice.

As you can imagine, this has the potential to undermine your rights in an enormous amount of information. It is common for the government to seek information from the third parties you have “disclosed” the information to–often email providers, telecommunications companies and ISPs. However, given how little many people know about the exact details of how their data is handled or disclosed it’s often a bit of a stretch to describe using an email server of something similar as “knowingly disclosing.” What’s more, this exact issue is something the Congress has already addressed to some extent through legislature such as the Electronic Communications Privacy Act, the Federal Wiretap Act and especially the Stored Communication’s Act (SCA).

To discuss these in full is the work of a textbook. However, the SCA is likely the most relevant to AG Sessions’ assertions and the protections on at least some of the data you “share” by using common online tools such as email or messaging services. A locked phone is almost certainly off the table in most situations–breaking a customer’s encryption is not only undermining a business’s entire brand but doing so at the behest of the government without a warrant is arguably unconstitutional. The SCA makes it similarly illegal for companies storing your online communications to disclose your data to the government in many situations, the data you store on your phone may often not even be disclosed from a source beyond the phone itself. Failure to comply with the SCA can lead to serious legal repercussions for the tech company violating the SCA’s rules.

What is the Stored Communications Act?

So obviously if a company doesn’t keep your communications private and it happens often enough the company will lose any credibility with the public and lose business. It makes sense that tech companies are careful with choosing whether to share user information and when to not just roll over. The SCA adds another consideration for these companies–providing a statutory source of protection like the protections of the Fourth Amendment for internet communications sought by the government and–in some cases–non-government entities. The SCA commonly applies to information such as emails and, after a 2010 court case–social media messages (but not open messages on a wall or comments unless the user is restrictive of access to these communications).

The SCA specifically protects the contents of digital communications stored on the internet as well as some appealingly non-content information which can be used to identify the contents of a communication such as subject headers. “Contents” is quite a broad legal concept and includes any information regarding the substance, import, or meaning of a communication. In general, however, non-content information can be disclosed without consent. Protected data cannot be shared with the government unless the person who made the communication consents to it.

If the information is less than 6 months (or more accurately 180 days) old the SCA applies the standards of a warrant before the government can access the information. After these 6 months are over, the standard of protection drops substantially and requires only a showing that the information could be relevant to an ongoing criminal proceeding. Routine business information such as location data–obviously not a communication–only requires a court order based on articulable facts for the government to demand it from a tech company.

The SCA makes it a crime to access without authorization or exceed authorization granted in accessing electronically stored communications. Where an ISP or company that stores your communications shares those communications in violation of the SCA they’re going to face serious repercussions. It can also create a civil action against both the company and the government for the person who made the improperly shared communication. It does not allow access to data stored outside the U.S. unless the user associated with the communications is a U.S. citizen.

Just over a month ago, Sessions’ own department strengthened the SCA. As written the SCA provides the ability for the government to impose gag orders on ISPs and tech companies–preventing them from even telling their user that they have disclosed their information. This is available with a government showing that such a notification would put a person or investigation at risk. The departments new approach limits the duration of these gag orders to one year and only if necessary. It also requires them to provide a more thorough explanation of why the gag order is necessary. The change is considered a response to a case related to the SCA brought by Microsoft last year. However, it certainly is odd to have the head of a department condemn protecting online privacy after his own department strengthened it barely a month ago.

Your Privacy is More Complicated Than AG Sessions Believes

Admittedly the SCA is not a perfect law, it doesn’t age with technology as well as it could and often relies on court rulings to update how it treats more modern technology–it isn’t even really settled how the timing of SCA protections apply if you don’t open an email. It doesn’t cover nearly as much as it could, and potentially as much as it should. Congress has not updated the law since it was originally passed over 30 years ago. However, it is an example of how the law values tech companies protecting your private data. To condemn tech companies for following the law is an unfortunate position for the government’s top lawyer.

The SCA and the Fourth Amendment are far from the only things limiting companies from disclosing user information or allowing access to an encrypted phone. Beyond the condemnation of the public if a company doesn’t keep your data safe and private, a company must follow its own privacy policies. Most privacy policies include carve outs for complying with court orders and it is far from uncommon to include provisions which state that a company will fully cooperate with any or some types of government investigation. However, this is far from a blanket truth. Where these carve outs don’t exist the release of information protected under a privacy policy would lead a company to face serious issues from the FTC.

While security and the investigations of the FBI are incredibly important, it’s far from unreasonable to expect the information you store online to have some privacy protections. In today’s world the sheer amount of information stored in this manner is mind-boggling. It is outright dangerous to the public to demand tech companies to relax their security protocols and Sessions demanding blanket access to the government is very nearly an irresponsible suggestion. Tech companies should be lauded, not condemned, for rigorously protecting the privacy rights of their customers.

Comments