Justice Gorsuch’s First Opinion, Creditors are Not Debt Collectors

The Fair Debt Collections Practices Act, or FBCPA, forbids debt collectors from harassing debtors, including using abusive language, make threats, call the debtor late at night or at work, or make misleading statements. The FBCPA applies to collection agencies and other third parties creditors may hire to chase debt. The FBCPA usually does not apply to creditors themselves, with a few exceptions. It is important that creditors and debtors alike know whether the FBCPA applies to their case, as the FBCPA allows the debtor to countersue if the debt collector violates the FBCPA.

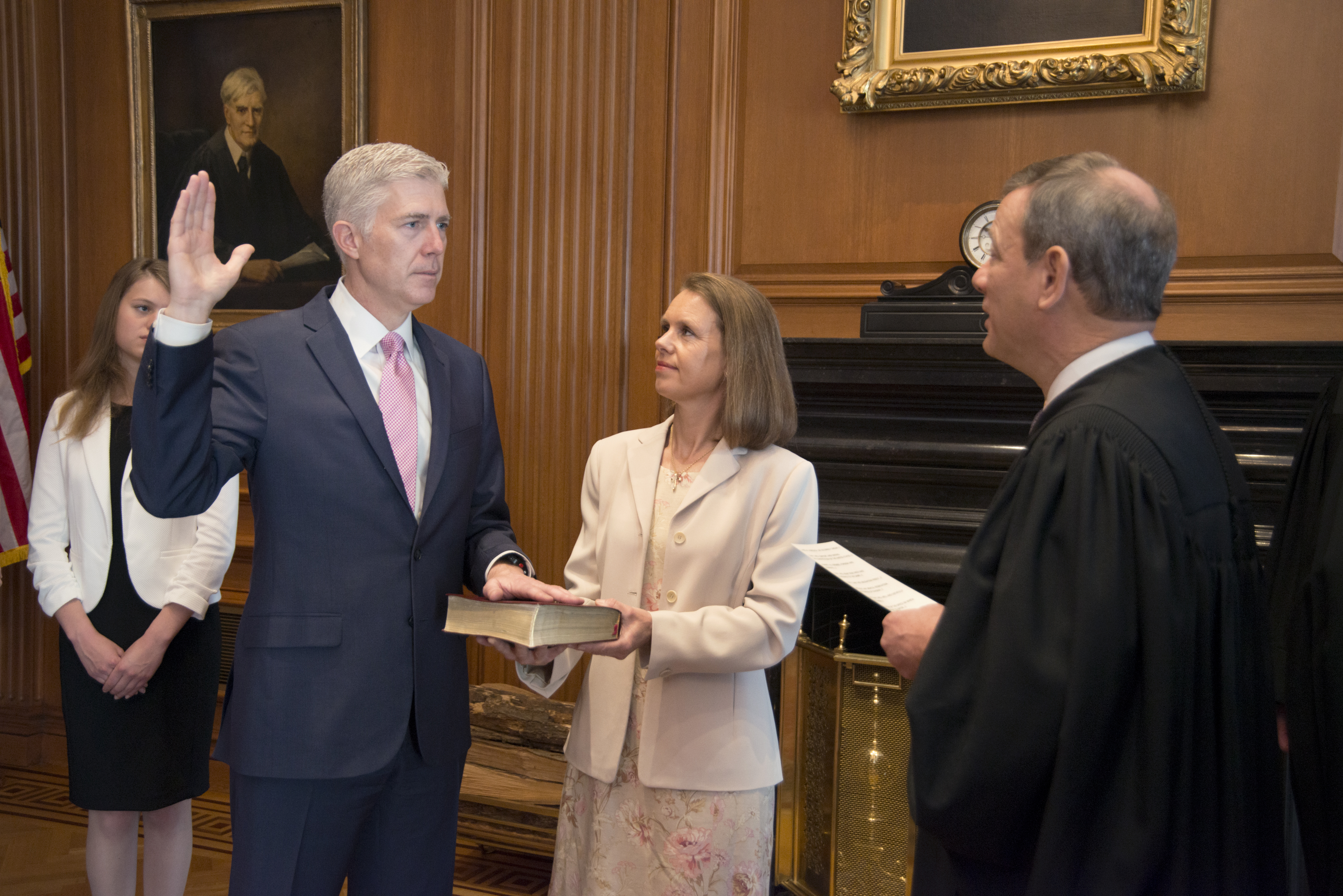

Justice Gorsuch’s first opinion deals with whether creditors who purchase debt from other creditors and pursue their newly purchased debts are debt collectors under the FBCPA. In Henson v. Santander, Citi Financial Auto financed a chain of car loans, which were purchased by Santander, a Spanish bank. Santander attempted to collect the loans and the plaintiffs sued, alleging that Santander had violated FBCPA by harassing and intimidating them. The Supreme Court ruled 9-0 in favor of Santander, declaring that creditors who purchase debt and then attempt to collect the debt themselves without a debt collector are not themselves debt collectors under FBCPA.

What Was His Focus?

What Was His Focus?

Justice Gorsuch focused primarily on the text of the Fair Debt Collections Act, which defines a debt collector as a person or business whose principal purpose is collecting “debts owed by another.” In other words, under FBCPA, a debt collector can only be a debt collector if the person is collecting debt on behalf of another person. If a person attempts to collect the debt on behalf of him or herself, that person is not a debt collector. Since that person is legally not a debt collector, FBCPA would not apply. Therefore, this person could use collection tactics that the FBCPA would normally prohibit, such as calling late at night or threatening the debtor.

Gorsuch’s opinion and the ruling of the Court are perfectly in line with the role of the judiciary in the Constitution’s checks and balances. Congress has chosen to write a law designed to protect debtors with a built in exemption for certain creditors. It is not the Court’s role to rewrite the law; if people have a problem with the FBCPA, they can ask Congress to change the law or vote in candidates who will change the FBCPA. With that said, the logic behind the law and the outcome of this case is disturbing. The FBCPA essentially states that debt collectors cannot harass debtors, but the owners of those debts can. If a bank like Santander wishes to use unsavory tactics to pressure people into paying their bills, those banks can save money and have greater options in pressuring debtors by cutting out the middle man.

So What Does this Mean for Us?

Arguably, this makes those banks more accountable if they forgo the debt collection agencies, but with the enormous market buying and selling debts, it actually makes it more difficult for debtors to figure out who owns and owes what. If I take out a mortgage with Bank of America, and Bank of America sells my mortgage to Wells Fargo, which sells my mortgage to Santander, I would have no way of knowing these purchases are happening. The resulting confusion on a mass scale could trigger a financial collapse, as it did in 2008 when the housing market tanked. The Court’s ruling and Gorsuch’s written opinion will encourage those same types of debt sales, as buying debt becomes not only more profitable, but easier to enforce legally as well. Congress must change the FBCPA to discourage these types of sales if we are to prevent another housing and financial crisis.

Comments