Criminal Conviction Overturned Due to Lack of Sign Language Interpreter

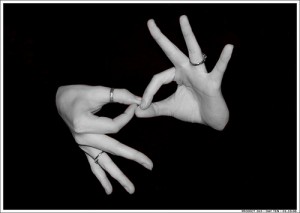

I’ve heard about plenty of cases where a criminal conviction has been overturned on appeal because of some impropriety in the courtroom. This is a new one: a deaf man convicted of a DUI had his conviction overturned on appeal, because he was denied a sign language interpreter during his trial.

Here’s what happened: after being arrested for a DUI, the defendant was put on trial. According to the law of Washington state (where the incident took place), criminal defendants who do not speak English are entitled to have an interpreter present during their proceedings, for an obvious reason: one of the basic tenets of due process is a requirement that the defendant understands the charges against him, and is able to participate in his own defense.

There did not appear to be any dispute that this requirement applied to deaf defendants who need sign language interpreters. However, the local criminal court did not have one available, and the judge, for whatever reason, ordered the trial to proceed. The defendant attempted to communicate with his criminal defense attorney via written  notes and lip-reading.

notes and lip-reading.

According to this article, the defendant’s hearing was completely gone by the time he was 9 months old. And it appears to be pretty well established that people who become deaf before 3 years of age have great difficulty learning language, and adults who lost their hearing at such a young age read, on average, at a 4th grade level, even if they are of average or greater intelligence in every other regard. These facts did not appear to be in dispute during the trial.

This case raises a few troubling issues for me. First off, why was a sign language interpreter unavailable for the trial? While I’m sure it’s fairly rare for them to be needed, it seems strange that the state court system wouldn’t at least have a few on call for when they are needed.

With state budgets taking huge hits in every area, it’s not surprising that local court systems have to watch their spending, especially because the courts are always an incredibly tempting target when it comes time to trim government budgets. After all, nobody likes going to court, and the popular image of the court system is that it does little more than enable frivolous lawsuits that cost businesses millions of dollars, and spends the rest of its time letting off criminals on technicalities.

Obviously, this image isn’t true, but when high-profile critics of the justice system argue for “reform” or budget cuts, they usually try to portray it in that light. I’m sure the fact that most of these calls come from moneyed interests who have the most to gain by gutting the judicial system is just a coincidence. But I digress.

My point was that that this case demonstrates why it’s very important to properly fund the criminal justice system. It may be tempting to cut corners to save money in the short run, but cutting court budgets doesn’t change the constitutional rights of defendants. And if those rights were compromised by a court that lacked the funding to do its job properly, there is probably going to be a lengthy appeals process, possibly costing the state more than it would have cost to simply hire a translator (or remedy whatever other structural problem gave rise to the appeal) in the first place.

Perhaps equally troubling, I fear that this case, and others like it, will lead to renewed calls from politicians to “get tough” on crime (strangely enough, we never call on politicians to be smart on crime), leading to reactionary and wrongheaded legislation that seeks to make such “technicalities” less likely.

However, whenever I hear people complaining about a criminal defendant getting off on a “technicality,” it usually sounds like they’re mad about the fact that the court followed the law. There are many rules that courts must follow, to ensure that criminal defendants get a fair trial. If a conviction results from a trial in which these rules weren’t followed, it’s only right for it to be overturned.

This gives courts an incentive to make sure that they follow these protections fully. If these rules had no mechanism for enforcement, they’d obviously be pretty meaningless.

So, if you’re one of those people who get angry when they hear about a criminal defendant getting off the hook for some reason not directly related to his guilt or innocence, read a little deeper and see what actually happened in the case. Then ask yourself, if you were in the defendant’s shoes, would you want the court to follow the rules that got his case thrown out? I’m going to go ahead and guess that the answer is yes.

Comments